Ghina . غنى

Ghina Mahmoud Al Kassem was only 13 when she started working as a sales assistant at a local shoe store in a working class neighborhood. Her employer never knew her real age. "I told him I was 17 and carried myself in a mature way. He even gave me a trial to see how I would communicate with the customers. I’m even shocked when I look back at my young self but I needed the job because I wanted to help my parents.”

During Ghina’s youth, helping others was instinctual. Aside from assisting her parents financially, she wanted to help the community. Back then it was in the small things - finding them what they can afford, or talking to management to adjust the price especially when she saw they had young kids. Adults were even seeking her advice and sharing their life troubles while having no idea she was a teenager.

It was there that Ghina met her husband, Ali, a Turkish citizen who was born in Lebanon to Turkish parents. Ali had gone in to buy shoes for his mom. A few years later they would get married. Ghina was 17.

Ghina’s father was hesitant when she told him she wanted to marry Ali. His first concern was hypothetical - what if they move to Turkey, away from the family? His second concern, however, would hit much closer to reality. Their future children would be Turkish citizens, not Lebanese which would cause them roadblocks while living in Lebanon.

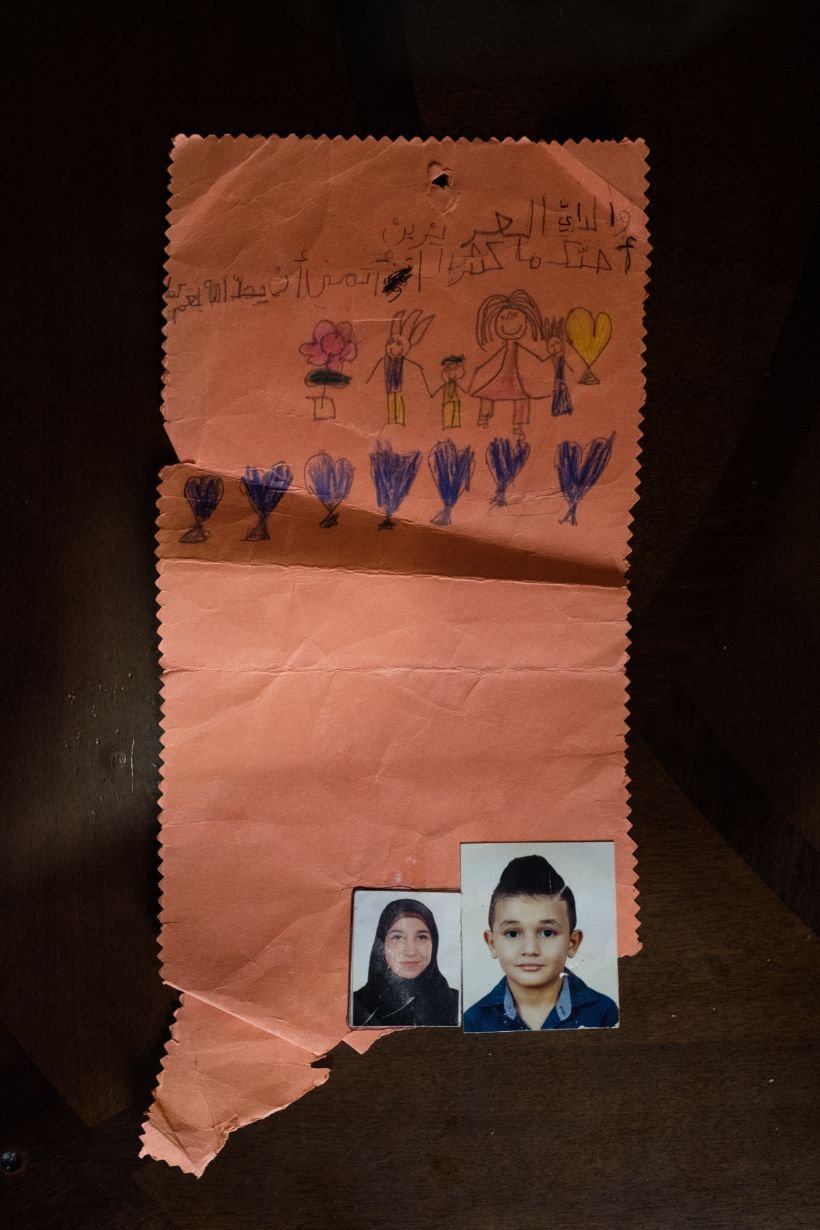

An outdated nationality law, left over from the French mandate, does not allow Lebanese mothers to pass their citizenship to their children or their spouses. Only fathers can. Men can also pass citizenship to their foreign wives as well as their stepchildren. Ghina didn’t grasp this fully until she had her first child and wanted to register him for school. The sexist law requires the children and the husband to renew residency papers every three years. Ghina describes the experience as humiliating. If you don’t have a “wasta” then you have to wait and even get ignored. The kids also have to miss school to go to the governmental offices to get their photos taken. They struggle with the idea that their mother’s national identity is different than theirs. As they grow older they ask questions about their different ID cards and wonder why they can never have governmental jobs in Lebanon.

The nationality law is one of many reasons Ghina ran for municipality this year with Beirut Madinati. She wants to see a change - make the future of the country better for her children and women in general. Her long list included opening educational youth centers and daycare for working mothers who wanted to continue their education.

“I got 6,000 votes. I wasn’t expecting it. Women can recognize issues and come up with solutions that men haven’t necessarily thought about. We are also physically strong. I work with the Civil Defense and oftentimes people ask me to step aside assuming they’re stronger but I handle everything as well as anyone.”

During the Israeli war on Lebanon in September through January of 2025, Ghina stayed in Lebanon even though the Turkish embassy evacuated her family via ship. She had been part of the civil defense for five years and felt she couldn’t turn her back on her comrades. “I couldn’t fathom the idea of feeling safe in another country given what my country was going through. It was risky but I felt responsible because I was trained for it. I couldn’t abandon. I didn’t think about being killed, instead I focused on safety and rescuing people.”

Ghina and Ali attempted to live in Turkey in 2020 after the Beirut Port explosion. Hoping to acclimate so their children can live in the country they have citizenship in. They sold their furniture and car in Lebanon to move. However, after three months, both of them realized they could only live and work in Lebanon. “It’s different culturally and language wise. We came back and had to start from zero in Lebanon again.”

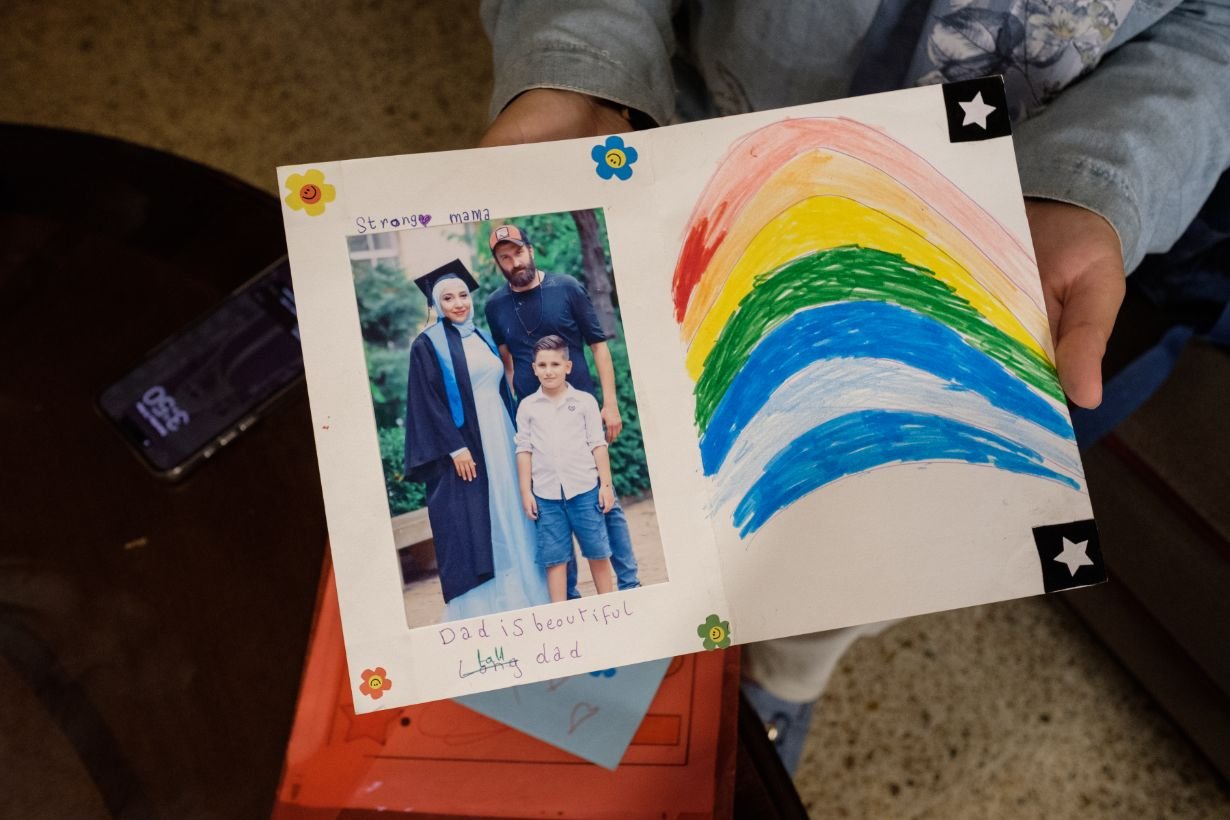

Starting over is not new for Ghina and her push for helping mothers continue their education isn’t accidental. After giving birth to two children, she wanted to go back to school and earn her degree. Her family didn’t sense the need. Through the years of working as a sales assistant, she had been promoted to assistant manager, and then to store manager. Her store was the top selling of 8 stores in the country. An achievement to be proud of. However, she consistently felt the injustice - the difference between people’s struggles in the working class neighborhood store compared to the privileges of the customers in the wealthy neighborhood. Her ambitions for self growth and doing more for the community wouldn’t cease. She started studying for brevet degree and her family quickly grew supportive seeing how she excelled. She smiles softly as she shows photos of her graduation with her kids before she entered university. “I got the brevet

degree on my own, then a degree in childhood education. Now I’m studying TS primary education, and I’m at the Lebanese University studying social sciences. So working on two degrees at the same time.”

For Ghina, making Lebanon stronger is the true investment of her life rather than conforming her life to living overseas. She finds opportunities to seed that strength in her every action whether it’s publicly like running for municipality, privately while volunteering with March Hona Beirut, or in her everyday life; “I teach refugee kids with Amel Association International. We have an educational guide to go by, of course, but we also have Social Emotional Learning, so I include teaching them about children’s rights to an education no matter what their race or nationality or religion or anything. It’s their right.”

كانت غنى محمود القاسم تبلغ من العمر ١٣ عاماً فقط عندما بدأت العمل كمساعدة مبيعات في متجر أحذية محلي في حي الطبقة العاملة. لم يعرف صاحب العمل عمرها الحقيقي. تقول: "أخبرته أن عمري ١٧ عاماً وتصرفت بطريقة ناضجة. حتى أنه أعطاني فترة تجريبية ليرى كيف سأتواصل مع الزبائن. ما زلت مصدومة عندما أنظر إلى نفسي الصغيرة آنذاك، لكنني كنت بحاجة إلى العمل لأنني أردت مساعدة والديّ."

منذ صغرها، كان مساعدة الآخرين أمراً غريزياً بالنسبة لغنى. فإلى جانب مساعدتها لوالديها مادياً، كانت ترغب أيضاً في مساعدة المجتمع. في ذلك الوقت، كانت المساعدة في أشياء صغيرة – كأن تجد لهم ما يناسب إمكانياتهم المادية، أو أن تتحدث مع الإدارة لتخفيض السعر خصوصاً عندما ترى أن لديهم أطفالاً صغاراً. حتى أن الكبار كانوا يلجؤون إليها ويشاركونها همومهم دون أن يدركوا أنها مجرد مراهقة.

وهناك، التقت غنى بزوجها علي، وهو مواطن تركي وُلد في لبنان لأبوين تركيين. كان علي قد دخل المتجر ليشتري حذاءً لوالدته. وبعد بضع سنوات تزوجا، وكانت غنى تبلغ من العمر ١٧ عاماً.

تردّد والد غنى عندما أخبرته أنها تريد الزواج من علي. كان قلقه الأول افتراضياً – ماذا لو انتقلا للعيش في تركيا بعيداً عن العائلة؟ أما قلقه الثاني فكان أقرب بكثير إلى الواقع: أطفالهما المستقبليون سيكونون مواطنين أتراكاً، لا لبنانيين، مما سيشكّل عقبات لهم أثناء عيشهم في لبنان.

فقانون الجنسية اللبناني القديم، الموروث من الانتداب الفرنسي، لا يسمح للأمهات اللبنانيات بمنح الجنسية لأطفالهن أو لأزواجهن. وحدهم الآباء يستطيعون ذلك. كما أن الرجال قادرون على منح الجنسية لزوجاتهم الأجنبيات وحتى لأبنائهن من زيجات سابقة. لم تستوعب غنى هذه المعضلة بشكل كامل إلا بعد إنجاب طفلها الأول ورغبتها في تسجيله في المدرسة. فالقانون التمييزي يفرض على الأطفال والأزواج تجديد إقامتهم كل ثلاث سنوات. تصف غنى هذه التجربة بالمهينة: "إذا لم يكن لديك واسطة فعليك الانتظار وحتى يتم تجاهلك. كما أن الأولاد يضطرون للغياب عن المدرسة للذهاب إلى الدوائر الحكومية لالتقاط الصور لهم. يكبرون وهم يعانون من فكرة أن هوية أمهم الوطنية مختلفة عن هويتهم. وعندما يكبرون أكثر يبدأون بطرح الأسئلة عن بطاقاتهم المختلفة ويتساءلون لماذا لا يمكنهم أبداً الحصول على وظائف حكومية في لبنان.

كان هذا القانون واحداً من الأسباب التي دفعت غنى للترشح للانتخابات البلدية هذا العام مع بيروت مدينتي. فهي تريد أن ترى تغييراً – أن تجعل مستقبل البلد أفضل لأطفالها وللنساء عموماً. تضمنت لائحتها الطويلة فتح مراكز شبابية تعليمية وحضانات للأمهات العاملات اللواتي يرغبن بمتابعة تعليمهن.

تقول: "حصلت على ٦٠٠٠ صوت. لم أكن أتوقع ذلك. النساء قادرات على ملاحظة قضايا وإيجاد حلول قد لا تخطر ببال الرجال بالضرورة. نحن أيضاً قويات جسدياً. أعمل مع الدفاع المدني وكثيراً ما يطلب مني الناس أن أتنحى جانباً باعتبارهم أنهم أقوى، لكنني أتعامل مع كل شيء تماماً مثل أي شخص آخر".

خلال الحرب الإسرائيلية على لبنان بين أيلول وكانون الثاني ٢٠٢٥، بقيت غنى في لبنان رغم أن السفارة التركية قامت بإجلاء عائلتها عبر السفينة. فقد كانت جزءاً من الدفاع المدني لمدة خمس سنوات وشعرت أنها لا تستطيع أن تدير ظهرها لرفاقها. تقول: "لم أستطع استيعاب فكرة أن أشعر بالأمان في بلد آخر بينما بلدي يمر بما يمر به. كان الأمر خطيراً لكنني شعرت بالمسؤولية لأنني تلقيت التدريب للتعامل مع هذه الحالات. لم أستطع التخلي. لم أفكر في احتمال أن أُقتل، بل ركّزت على السلامة العامة وإنقاذ الناس".

في عام ٢٠٢٠، حاولت غنى وعلي العيش في تركيا بعد انفجار مرفأ بيروت، على أمل أن يتأقلموا ليعيش أطفالهم في بلد يحملون جنسيته. باعا أثاثهما وسيارتهما في لبنان للانتقال. لكن بعد ثلاثة أشهر فقط، أدرك كلاهما أنهما لا يستطيعان العيش والعمل إلا في لبنان. تقول: "الاختلاف ثقافي ولغوي. عدنا واضطررنا للبدء من الصفر مجدداً في لبنان".

لم يكن البدء من جديد أمراً غريباً على غنى، ودفعها لمساعدة الأمهات على متابعة تعليمهن لم يكن صدفة. فبعد إنجاب طفلين، أرادت العودة إلى الدراسة والحصول على شهادتها. لم يرَ أهلها ضرورة لذلك. لكن بعد سنوات من العمل كمساعدة مبيعات تمت ترقيتها إلى مساعدة مدير، ثم إلى مديرة متجر. وكان متجرها الأعلى مبيعاً من بين 8 متاجر في البلاد – إنجاز تفخر به. ومع ذلك، شعرت باستمرار بالظلم – الفارق بين معاناة الناس في حي الطبقة العاملة الذي كانت تعمل فيه وبين امتيازات الزبائن في الأحياء الثرية. طموحها للنمو الذاتي وخدمة المجتمع لم يتوقف. بدأت دراسة شهادة "البروفيه" وسرعان ما أصبح أهلها داعمين لها بعدما رأوا تفوقها. تبتسم برقة وهي تُري صور تخرجها مع أطفالها قبل دخولها الجامعة. تقول: "حصلت على شهادة البروفيه بمفردي، ثم شهادة في التربية الحضانية. والآن أدرس TS في التعليم الابتدائي، وأنا في الجامعة اللبنانية أدرس العلوم الاجتماعية. أي أنني ادرس اختصاصين في الوقت نفسه.

بالنسبة لغنى، جعل لبنان أقوى هو الاستثمار الحقيقي في حياتها بدلاً من تكييف حياتها للعيش في الخارج. فهي تجد دائماً فرصاً لزرع هذه القوة في كل فعل من أفعالها – سواء علناً بترشحها للبلدية، أو بشكل خاص من خلال تطوعها مع مارش هنا بيروت، أو في حياتها اليومية: "أعلّم أطفال اللاجئين مع جمعية عامل الدولية. لدينا دليل تعليمي بالطبع، لكن لدينا أيضاً التعلم الاجتماعي العاطفي، لذلك أحرص على تعريفهم على حقوق الأطفال في التعليم بغض النظر عن عرقهم أو جنسيتهم أو دينهم أو أي شيء آخر. إنه حقهم".